Start Up Board Governance

by Claudia Heimer and Sophie Linguri Coughlan

Photo by Dane Deaner on Unsplash

As a founder, why would you spend any time thinking about governance? Aren’t you better off focusing your attention on product development, expanding your user base, building new revenue streams — or considering pivoting to a new business model when your customers show you a new path? Governance is the last thing on start-up founders’ minds. Or so our experience of working with entrepreneurs shows. The pressure of succeeding until the next round of financing — whether it’s by demonstrating early-stage proof of concept, or later-stage, scaling up — makes for an all-consuming focus on growth.

While it is tempting for time-starved entrepreneurs to ignore the need for governance, we think this is a grave mistake. The press is full of examples of poor governance leading to the demise of promising ventures. Ignoring governance not only increases the risk of financial irregularities and other serious compliance violations but also errors in judgement which may prove fatal.

One of the most critical board failures in recent times involved a venture founded by Sam Bankman-Fried. The sudden collapse of the cryptocurrency exchange FTX in November 2022 revealed a dearth of due diligence and oversight from major investors, including Sequoia Capital, who invested $213.5 million. Another major founder-led failure was Theranos, the blood testing start-up that raised more than US$700 million from venture capitalists and private investors and had a $10 billion valuation at its peak. Elizabeth Holmes was convicted in 2022 of convicted of wire fraud and is currently serving an 11-year prison sentence. . WeWork’s failed IPO attempt in 2019 revealed significant governance issues under founder Adam Neumann’s leadership. The company continued to face challenges, culminating with a bankruptcy filing in November 2023 — and costing investor Softbank $14 billion.

While not a start-up itself, Silicon Valley Bank’s collapse in March 2023 highlighted governance issues in the broader start-up ecosystem, particularly in risk management and oversight of financial institutions serving the tech industry. Clearly, for too long, an obsession with charismatic founder personalities and compelling start-up pitches has led to ecosystem-wide blind spots.

No matter through which lenses you view these spectacular failures, from the perspective of founders or of investors, it boils down to the same point. Good governance protects founders against these pitfalls, whether the self-harm was by design, delusion or default. It also protects investors from fraud and mismanagement. Governance, since the Silicon Valley Bank meltdown, is increasingly seen as a quality mark for an investable start-up. Today, governance not only ensures that founders are held accountable and receive proper guidance. It also builds trust with customers and partners, attracts high-quality talent and prepares the company for future growth and a potential public offering.

As board educators, coaches, advisors and members, we have both often come into contact with start-up founders who have been burned by bad governance experiences. And yet, the prevailing corporate governance wisdom seems ill-adapted for the rapidly changing context of start-ups and their need for agility. As practitioners in a knowledge field that is still emerging and has little academic foundation, we are ready to contribute our insights about governance for entrepreneurs — and to engage in a discussion in this rapidly evolving field.

What does good start-up governance look like? We sympathise with the view that established governance models are generally not well adapted to the realities of start-ups. They are overly elaborate for the resource-limited, specific situations entrepreneurs find themselves in. In this article, we suggest a practical way forward, grounded in governance expertise, yet adapted to the needs of founders and their backers.

Let us start with defining what governance means to us. We subscribe to the definition of governance that Founder of the IMD Global Board Center Professor Didier Cossin posits, that governance is the art of making good decisions at the top of organisations. If we take this simple yet compelling idea as our basis, why would any start-up, why would any investor not want to ensure that decisions are of the highest quality possible? If we assume this as being desirable, how do we make governance work in a fast paced, highly innovative, entrepreneurial environment? An environment that requires room for error and innovation, which most mature governance frameworks protect a company against?

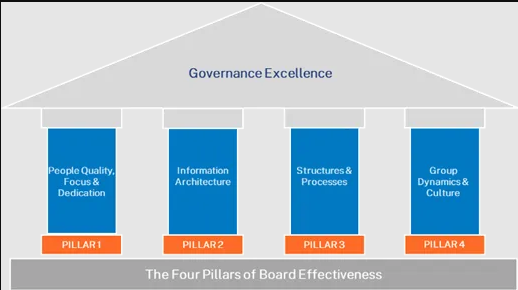

While we have often heard founders say that they plan to add governance at a later stage of maturity, we take the view that governance needs to be built into from inception — in prototype form, adaptable throughout the various stages of start-up lifecycle maturity. Here, we will discuss the value a board can add to a start-up, and methodologies to evolve your start-up’s governance model using our Minimum Viable Governance framework. We will share our thoughts on how to build your board, conduct your due diligence to appoint directors, onboard your members and conduct the first meeting. To us, governance is a dynamic process and requires evaluation to ensure it is aligned with your needs. It requires review at specific intervals, so that it evolves with the company. The Four Pillars Model of Board Effectiveness (Cossin, 2020) is a tool that we find helpful at any stage of a company’s development.

Once you apply the fundamentals of start-up governance, how do you ensure your board is future-ready? Most start-ups tend to use their networks and communities to compose their boards with people who bring complementary competencies and connections that they need to grow and prosper. Yet a board is more than the sum of its parts. Even experienced, senior non-executives who have shaped industry trends, let alone made successful exits in the past do not guarantee a board that is cohesive, builds common understanding and makes effective decisions. This requires fostering a board culture that is productive, able to properly read changing circumstances, adapt quickly to seize opportunities, as well as mitigate against risk. So, how do you keep looking forward, rather than settle back into past formulas for success? Particularly given that start up advisors and investors bank on their experience? How do you keep challenging everyone to anticipate the future and prepare for different scenarios, particularly for start-ups that are creating new categories?

Today, we can use technology to protect investments and maximise value by ensuring that a board is truly future-ready — as a whole. FitBoard developed technology to help boards stay alert and future oriented — all year long, well beyond the annual strategy retreat. External and internal signs in and around the boardroom are processed and flagged up to the board in real time, leading to actionable recommendations so that the board can come together well and stay ahead.

1 Here’s the value a board can add to your start up

Boards are not a priority for most start-ups. Many founders see board members as either too busy, too far from their reality to really “get it”, pushing them too hard, or trying to get them fired before they even had a chance to prove themselves. Founders often ask us: “Is there a way to free us from this burden?” At the same time, investors wonder, “Can you help make it less painful?”

What then is the value a board can add to a start up? Why should you bother, beyond the minimal legal requirements? We both experienced building entrepreneurs’ boards first- hand as a challenge, yet they are also an opportunity if approached with intent. We look at three key areas from which start ups can benefit:

1) Resourcing

Consider your board as a magnet for top talent and partnership acquisition. A board can help a start-up to engage advisors with capabilities they might be missing. It can attract talented team members who might otherwise not consider the company interesting enough for them to join full time. Board members with great standing in their communities can mobilize potential investors who will take their lead. They can also open doors, given their credibility and access, helping with customer acquisition. A powerfully composed board can open up strategic partnership opportunities, which can act as channels for growth in terms of business development or joint research & development for further innovative solutions.

2) Strategy

Whilst start up founders must focus on building the enterprise, their board can help with maintaining strategic foresight. A board can help shape strategy, point out blind spots in the founders’ strategic thinking and highlight issues in strategic execution. Boards can take three stances (Cossin, 2020):

Supervising — checking for founders’ quality of thinking, from strategy formulation to strategy execution, grounding it back in present progress towards KPIs whilst keeping eyes on technological and market development.

Co-creating — investing time in collaboratively crafting strategy with the founders, from analysis of trends to strategy development and review, deep diving into all aspects of data analysis, checking for assumptions and keeping strategic goals on the horizon.

Supporting — hands- on support of management’s business plans and go-to-market, whilst founders are in the lead, validating and publicly supporting avenues for growth, even in the press and social media

Start-up boards develop an approach that shifts between all three stances, depending on the strategic context as well as the maturity of the enterprise. Experienced board directors will be able to ask good and challenging questions in supervisory mode, to make sure that management isn’t missing something vital as they forge their strategy and develop or refine their go-to-market plan. Board directors with experience and expertise that is directly relevant to the start-up will be able to co-create strategy with the founders. Regardless of their level of experience, board members will be able to support management in making their thinking robust, as well as lending an ear or hand during the inevitable tough times — and advise them to pivot when appropriate. Whilst listed companies can be constrained by jurisdiction-based legislation, pre-IPO start-ups can allow for more fluidity between the three stances. Actively mapping the different contexts and circumstances the board can play a strategic role, and in which capacity, allows the founders to receive the value they need from the board — where and when they most need it.

3) Risk management

The board is the best placed group to identify and monitor risks that are invisible to founders. From the board’s vantage point, risks look different than they do from the start-up’s engine room. By taking a longer-term — and more systemic- perspective, board members may identify risks which are fundamentally different in nature — i.e. strategic or systemic. They may also play a role in challenging biases that founders may be falling pray to. Entrepreneurs, by definition, must bring an above-average capacity for optimism, wellness, resilience and happiness –, in order to succeed. The start-up is their baby, and emotions are tightly wrapped up in day-to-day decision making, as well as in setting up tracks for a new strategy. The board can help the founding team watch out for, prioritize and contain financial risks, operational risks and reputational risks.

2 Evolving your start-up’s governance model using our Minimum Viable Governance framework

Entrepreneurs ideally have a fully-fledged governance framework in mind from the start. Yet they set out with what we call a Minimal Viable Governance Framework. It pays to put some effort into understanding the fundamentals of governance before designing your own framework, otherwise you risk leaving glaring gaps. You can then be more pragmatic when it comes to fleshing out a model that is adapted to your needs and context.

“Governance needs to grow with the start-up, rather than be an afterthought, when you run into problems. At this point, it might be too late.”

Any theoretical foundation for the design of a governance architecture, whether you consult books on the topic, or attend educational programmes will provide you with a good overview of what you need consider. Try to avoid cutting corners by going to an advisor with a single functional area of expertise. This will make you buy the advice, and the advisor’s biases, whether financial or legal, for example. You must know at least the basics of governance to make a good start.

Consider this. Lawyers will typically advise you to focus on three documents, after which your set up is considered complete:

A pre-incorporation Memorandum of Understanding between the founders of the company (including any founding partners on the investor side), helping to clarify and set down mutual expectations, starting with the vision for the company, the culture you wish to foster and a basic set of rules of decision-making you anticipate.

Articles of Incorporation in line with the jurisdiction-specific legislation and governance codes, and in line with the Memorandum of Understanding, setting down the purpose of the company, the rights and duties of directors, the company’s organization and governance structure.

The Shareholder Agreement, including agreements as to the rights and duties of shareholders, the agreed shareholder meeting set up and frequency, agreement on terminations, good leaver and bad leaver provisions for the joint risk taking in the venture.

When considering the risk profile of entrepreneurial ventures, this legal starter kit is necessary but not sufficient. Research into the success or failure of start-ups consistently flags conflicts between co-founders as one of the most crucial make-or-break factor for a start-up. This is why, alongside the legal starter kit, we highly recommend that the founding team establish the key governance muscle they will require for the entirety of the journey.

Build your MVG framework, based on the best practice 4 pillars of good governance (Cossin, 2020) working through the following checklist we put forward for start-ups:

Pillar 1) People

What strengths can you build on within the current board members, bearing in mind your strategy and maturity stage?

What capabilities that you already have on your board can you now begin to leverage?

What key skills and competences are missing in the current composition of your board?

What kind of talent or experience must you bring into your board, considering your ambition in the longer-term?

Do you have diversity in terms of personalities and thinking styles?

Is there a risk of in-group/ out-group bias? Is there sufficient diversity to guard against members aligning on dimensions such as gender, background or even founder/investor / independent board member?

How much time and bandwidth do your board members give to the company?

Does the board require more focus and dedication from your board members to help the business reach its next milestones?

Pillar 2) Information architecture

Are you confident that you are getting the full picture of the state of the business?

Do you have the right level of information to understand the implications of strategic decisions — both in terms of risk and opportunity? How do you know?

How are you keeping your ear to the ground in the company today, informally?

Are you satisfied that you are sufficiently keeping up with external stakeholders who can help you fill in potential strategic blind spots? (regulators, customers, industry experts…)

What kinds of informal networks do you have in place to access strategic information?

Are there information sources for competitive intelligence, geographic and technological developments) that would help you and the board in the upcoming strategy review cycle?

Pillar 3) Structures and processes

Do you systematically take the time to step back from the operational business to reflect at a strategic level, and ask the big questions (is it time to pivot, change course, initiate new strategic partnerships, M&A, exit)? If so, how? Can this be improved?

How are you doing on stakeholder engagement? This could be suppliers, partners, customers or contractors as well as regulators or even competitors. Are you up to date with their thinking — and they with yours?

Do you have enough financial and audit expertise, and are you ensuring that you are using them when needed?

Is there a risk of fraud or integrity failures? How do you know?

How are you ensuring that your structures and processes track your maturity level?

4) Group dynamics

What are the discussion styles your board has developed? What are their positives, and what are the drawbacks of these styles?

How do you rate the level of safety in your discussions?

How comfortable are you with holding onto tensions and disagreements? Could you be avoiding conflict?

What decision-making styles do you favour? How do you guard against bias?

Do you review your most important decisions and their underlying assumptions decisions?

Do founder voices dominate the conversation?

Are you hearing dissenting voices enough?

Are board members providing enough support, or is there a tendency for founders to be continually grilled?

Is there an “us & them” dynamic between founders and board members?

Workshop this checklist within the co-founder circle, at the very start of your venture together, and then take your resulting decisions to your most trusted advisors. Ensure that you go beyond the typical circle of lawyers and include experienced board members, and people with founder experience. Once you have validated your thoughts with a group that has a rounded, cross-functional and cross-hierarchical perspective, consider this your MVG and iterate as you reach liquidity events or other major milestones.

3 How to build your board

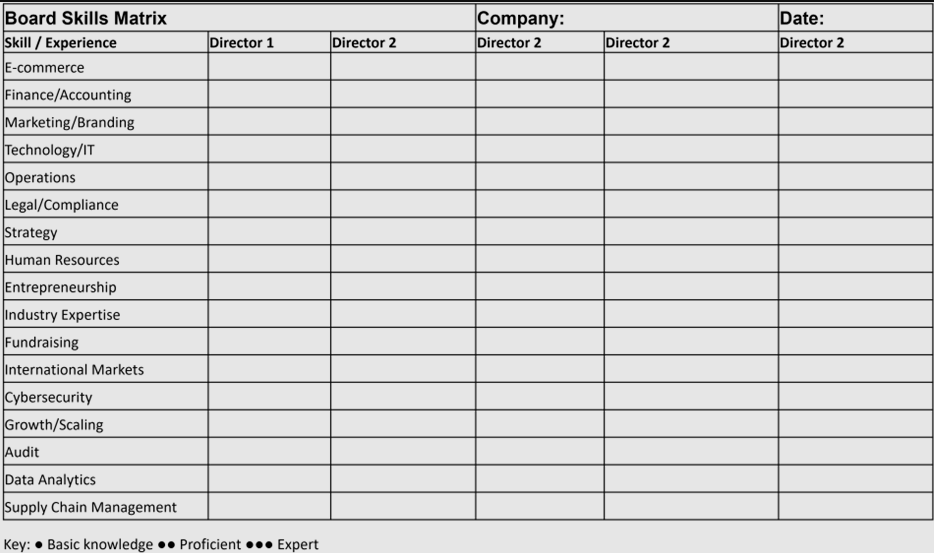

How do you go about building your board, so that it helps you scale and grow? First, you need to think about the skills, resources, cultural codes and readiness to engage with you that an ideal board member might bring. A helpful tool for building your board — ensuring that at least at first, and in theory, without any egos getting in the way — is to develop your board skills matrix. Identify the skills and attributes that will be critical to your business not only in the early stage, but also as it grows in maturity.

Template by Claudia Heimer and Sophie Coughlan

Our skills matrix is designed to provide a visual representation of the collective expertise and experience of the board of directors you wish to build. It can be used not only for assessing a current board but also for identifying ideal candidates when new board positions open up. The matrix should be a living document, with skills and attributes that are aligned with your strategy, and reviewed and updated regularly as the start-up evolves and faces new challenges.

To get started, you can begin by looking at the current state of your board, if you already have one. Or, map out what the business will require in future based on your strategy. These are the three applications of the tool:

1. Current skill mapping: It clearly shows the distribution of skills across board members.

2. Gap analysis: It helps identify areas where the board might lack expertise or diversity — currently and over time.

3. Future skill mapping: ensure you align board competencies with company’s strategic goals.

Keep your strategy and culture in mind as you work on your ideal state matrix. Use our RSR model to deep dive into what you require in terms of:

1) the resources to help your venture grow, articulating clearly and precisely what expectations you have of your board members, so that you can formalize them in your Memorandum of Understanding, ahead of their joining your legal board more formally.

2) the strategy mindset which you want to determine for your board, in your board charter, and the skills and emotional intelligence this will, in turn, require of the board members.

3) the risk expertise and perspective you want your board to provide, which will drive your scrutiny of your board members’ deep functional expertise allowing them to “read”, spot and help mitigate operational, conduct, and reputational risks at the level of granularity that matches your start-up’s maturity stage — as well as more systemic, long-term risk where needed

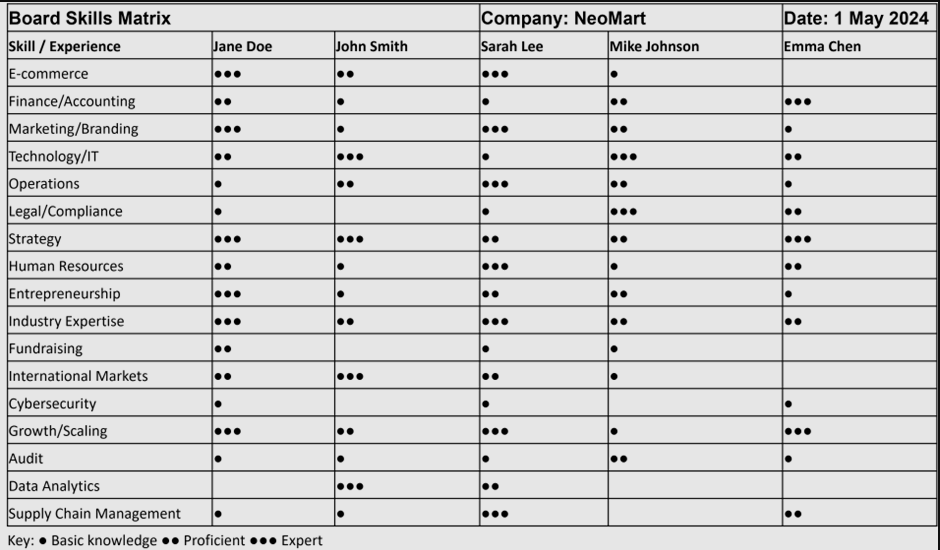

In this completed example, we have a diverse board with complementary skills, as they might embark after a successful funding round with a start-up’s first professional investors:

Jane Doe: E-commerce expert with strong marketing and entrepreneurial background

John Smith: Technology and finance specialist with international experience

Sarah Lee: Operations and HR expert with deep e-commerce and industry knowledge

Mike Johnson: Legal and compliance specialist with technology expertise

Emma Chen: Finance and fundraising expert with strong international market knowledge

This is important preparation to begin an all out recruitment campaign for the best talent for your board. Do not become disheartened by views that you will have to accept and live with just anyone your investors put forward as their representatives. Just as you don’t go into any business negotiation as a submissive partner, do come fully prepared to the conversation about your board’s composition. Once you have presented a clear rationale for how you would like your board to be designed, you will have a much stronger position with your co-owners. At the very least, insist on one, if not more independent directors to avoid too much role conflict designed into your board. If your prospective investors put up resistance, this is a massive red flag. Tread carefully.

Next, think about how you want to attract and screen the right board members for your board. This is no longer the time to turn to your family, friends and fools. You must think twice about inviting anyone. They might or they might not serve your company best. Just as any investor completes a due diligence before investing in a start up, you must create your own due diligence checklist and check any future board member to make sure they are value creators rather than value destroyers for your business.

Once you have clarity on the candidates you would like to bring into your board, we highly recommend that you agree a period of what we call “embedded due diligence” into your process of building an effective board. Treat this as both an onboarding phase, as well as a trial period for your board member. A single board member can make or break your start-up. They can set it back by 12 months or propel it forward by 12 months. This might be simply through their power of asking the wrong, or the right questions. A thorough nomination process will take you far, but it is only necessary but not sufficient. Psychometric assessments, whilst well established in hiring for large enterprise, are rarely used to appoint start up board members. How else can you uncover the way your board members will act under pressure? Joining the board as observers before any legal confirmation is common practice in the start-up world. Why not propose this by design, so that both sides can find out if there is a good fit? Any prospective advisor or board member who feels disrespected or triggered by such a proposition is raising a big red flag. If their ego cannot stand anything other than being hired on the spot, something might well go wrong when stakes are truly high.

Ideally, all your relationships with prospective board members need to start with a more informal period within which they act as advisor to you, one of your co-founders or team members. Your initial chemistry check, your initial due diligence might have worked very well. Now, you will see the advisor in action, initially one on one. How do they behave in the third, in the fourth meeting? Put them in a group situation as soon as you can, to see how they perform. It is only when you are in the real situation that people really show themselves — ideally when a little pressure is there on everyone. You might find that a highly qualified candidate with a great track record performs poorly. You need to be able to choose, and to let them go if they are not right for you.

In our experience, poor performance by advisors with great track records is most often due to executives accustomed to resource-rich world of large enterprise when you are still fighting the scrappy life of a hungry start up. There is also the case of family business owners, who on paper appear to be a wonderful choice to help you enter a particular market, but may have not been able to shed obsolete paternalistic management ideas about how businesses should be run. These may come out as toxic attacks — seemingly from nowhere — when they feel under pressure. They might have gone through a family business bankruptcy which they are not yet de-traumatized from. And so, they have a paranoid response in your board meetings, hijacking agenda item after agenda item. They might have little to no experience as a founder. And so, very little understanding — nor empathy — for life as a start-up founder. They might have multiple exits under their belt, as serial founders themselves, but despite loving your business model, your story and hanging out with you in coffee houses, they have not owned up to themselves — let alone you — that they no longer feel like reading board packs and showing up for formal board meetings. They would much rather be windsurfing.

Instead of leaving things to trial and error, use the simple device of the embedded due diligence for 3–6 months, structured into your MoU with your advisors. Somewhere in that period of embedded due diligence, you might form an advisory board. Or you might move directly to building a board with the key skills you required. In any case, it is a very good idea to road test your advisors, before you proceed.

4 Conducting your first board meeting

It is important to actively design your first board meeting, as a way to build the culture that you want. Individual board members will have their own views about what they believe their role is- and your role is. Some will see themselves as your supervisors. Others will see themselves as your coaches. A board charter is a useful tool to guide your board on what you want them to do and how you would like them to fulfil their roles. Do not cut corners or let the lead investor send you one that she has prepared earlier. Ideally, set a pre-meeting, ahead of your first formal board meeting, to validate your draft board charter, make any additions your prospective board members request and ensure that you start on the journey aligned and clear on the mutual expectations between you as the founder, and your board. In this way, a pre-meeting can serve as a collective onboarding, setting the ground rules for how you will interact with one another.

As you prepare for the first board meeting, ask yourself: who should lead it? To us, it is the founding CEO’s job to lead the board in close cooperation with the Chair. As you prepare for your first board meeting, think about what you want the outcome to be. This is no longer a due diligence meeting, or part of the final negotiations of a funding round. There is no need to persuade anyone. There is no need to grill anyone. There are technicalities to observe depending in your jurisdiction, and on the requirements of outside investors, if the venture is not fully bootstrapped by the founders.

In case a pre-meeting (as described above) is not possible, your first board meeting will serve the purpose of onboarding, ensuring clarity around definitions and metrics used in the company. Each director will have their own picture of the company, following their own due diligence process. This picture will be biased by their own preferences, ways of thinking and their area of expertise. The first meeting is the opportunity to put the pieces of the puzzle together, and come out with a shared understanding of where the company is, and where it plans to go.

Your objectives for the first meeting may be different than those of your board members. There is no rule book, so it is important to be clear on what you want to achieve, to help you manage potential variance in expectations. Depending on the culture you want to set for the board, the first meeting might concentrate more on an introduction of each Board Director and how they think. It could involve a clarification of the purpose of the company and the mission of the board, set out in your board charter, (which needs to be the first document prepared by the CEO and the Chair ahead of meeting). It might include the review of specific aspects of the strategy, or the technology roadmap. It will include, as any subsequent board meeting, business updates and forecasts, followed by discussions of a few substantive issues in more depth.

A few critical questions you need to clarify are:

A) How the agenda of the board meeting will be set. Ideally, the Chair or the CEO set out the agenda, agree it with one another, and then run it past the board ahead of the meeting. If you use a file sharing drive, or plan to introduce a highly secure board portal, you will be easily able to collaborate with the board on agenda setting. Make sure that whatever happens, everyone expresses their interests in topics, but that you retain control over what is ultimately on the agenda. You will only have a limited amount of time with the whole board, and it is important to concentrate on the topics that will best serve the company. Requests by board members can also be handled off-line, one-to-one, or via a field trip for directors interested in informally meeting the team and visit the operations.

Start the agenda with the 2–3 substantive issues you would like to cover. Conclude with the less important times. Examples for the former are:

Do you anticipate a change in your business model?

Do you need to review a key partnership that might be underperforming?

Do you wish to discuss the timing for a new round of financing, so that you can enrol the board in starting conversations early?

The usual flaw we see boards fall for when we review their performance is spending too much time on procedural topics and then running out of time for the value-add dialogue.

Instead of listing topics, we encourage founders to formulate outcome-oriented objectives. If all that is required for a topic are one-way updates to make sure all directors share a common understanding of the state of the business, state that. Each director can otherwise interpret their brief differently and start inquiring deeply into each topic in problem solving mode, because this is what they have been doing all their professional life. Be clear: do you need help on a particular topic? Do you want to acid test an idea by making sure the board challenges a proposed approach to make sure you have looked at every angle? State that. Do we seek a free flowing, creative deep dive on a strategic matter that does not yet require immediate decision making? State that. Shape your agenda by being clear on what you want to get out of each section.

B) The shape of the board pack and the deadline for its delivery to the board. Regarding the shape of what you provide to the board in preparation for the first meeting, it is a good idea to start how you aim to continue. A useful structure is:

· Cover sheet setting out the objectives of the meeting, and the topics for discussion, as well as information on the logistics

· Executive Summary with an update on the previous business period, and the reflections of the CEO (1–2 pages)

· Framing papers to introduce the 2–3 substantive topics for discussion, outlining the key issue, the decision to be made, the options considered, as well as the risks and opportunities perceived (5–10 pages)

· Back-up documentation including more detailed reports relating to the company updates, minutes of previous board meetings to prepare their sign off, and any background, financial analysis or additional information to help board members prepare for the 2–3 substantive topics

At the beginning of the start-up’s journey, the board pack will of course be smaller. The key is to develop the discipline of framing the topics, and preparing them well. The clearer directors are guided by the founders on how they would like to tackle a topic, the more productive the meeting will be, and less dynamics or ad libitum excursions by unprepared directors will get in the way of a valuable discussion.

Make the board pack clear and focused on the substantive issues, rather than flashy. This is the single most frequent complaint we received from start-up board members. Investors and directors read more PowerPoint files, pitches and presentations than they would like. Using word instead of slides can be very welcome and refreshing. Work out a model with the Chair and improve it continually based on the feedback you receive from board members.

Board packs delivered in under 48 hours before a board meeting are disrespectful to the directors. Depending on their thinking preferences, some will require more time to process the information, and let your framing of the topics sink in. Others will be quicker on their feet yet will still want to plan their time before the meeting. Board packs sent to board members 7 working days ahead of time are rare, because they are so fast moving. You can work around the pressure of the deadline by uploading as much as possible onto your online board repository as soon as it is ready. Ensure that directors receive notifications when you do.

C) How you will be Chairing the first meeting. If the Chair and the CEO have jointly and individually prepared well, the board meeting can be chaired effectively between them. The Chair holds the space and moderates the flow of discussion along the agenda, the CEO or the topic leader direct the conversation along the way that it has been framed. Even in a first meeting, the Chair can hold regular pace checks to ensure that everybody was able to contribute, questions and concerns have been raised, that there was no undue rush or overly protracted conversation without substantially moving the board forward. Alignment checks are useful so that no assumptions are being made about when key decisions are taken.

The earlier the board becomes used to reviewing its meeting, as soon after it closes, and directors have been able to reflect on it, the better. This way, the Chair can ensure that the style of facilitation works well to keep the meeting focussed and everyone engaged. The same goes for the board pack and the minutes of the meeting: the earlier you can gather feedback on whether the style is working for the directors, the better you can improve them.

D) How soon you will introduce “executive sessions”. Meaning, closed meetings of the board without the founders or C-suite leaders. In some contexts, this is an intervention of last resort. In others, it is part of the board charter and allows for the board to fully clarify any vital, open questions as well as its collective response to management. The key here is to agree this upfront with the founders to avoid any unnecessary tension or dysfunction later on. There is no counter indication for starting with the practice right away. Under no circumstances is it a good idea to start out the journey of a board by surprising the founders with an executive session immediately following a first board meeting.

Board meetings are a formal requirement when you set up your legal board of directors. Yet their purpose ultimately is to help the CEO keep on track. By setting your meeting practices well, you will be building the governance muscle that will help attract (more) funding, new high-calibre advisors and board members in future.

5 Boost your growth by upgrading your board

Once you have had your first meeting, immediately start assessing your board. Far from declaring victory because you assembled a board packed with talent and experience, access to customers and future investors, nothing guarantees that this diversity will work in your favour. You have created an onboarding programme for the people in your company? Your board members need the same. They need to bring themselves to the table, in a new constellation and deliver a professional service that can make or break your company. Why should they not require help in achieving that? And how can you best structure this process? What are the pitfalls? What are the drivers of good governance that can set you up for business and boardroom success?

We use Didier Cossin’s four pillars methodology (mentioned above) as a helpful framework to structure and adapt a start up’s governance, from the principles backed by his decade-long research into what makes companies not only thrive but sustain themselves across generations of owners — and how effective boards are instrumental to performance. The four pillars can help you assess your board, as the company grows and places different requirements on board members and your overall board set up. Use our checklist from early stage onwards, as a way to evaluate and upgrade your board quality.

Pillar 1: People Quality, focus and dedication

At the very early stages of your start up, you will not need an ideally composed board beyond the founders. You are likely to choose, and benefit from having a set of individual advisors. A changing set of advisors adapted to the different stages in the company’s growth and corresponding change in requirements. Even when it comes to choosing your advisors, it is wise to look at them through the lens of good governance. Consider that they will be, together with you, determine what you will prioritize, and what the cofounding circle will decide. They might, or they might not qualify to become board members later, and many do hope and even push hard for board seats on your start up, so you will need to manage those expectations as early as possible.

Quality:

You might think developing a skills map for your advisors is overkill. To us, it is never too early to start. Having a systematic approach to attracting, searching, and assessing your advisors and potential board members will help your credibility with successful, professional start up investors.

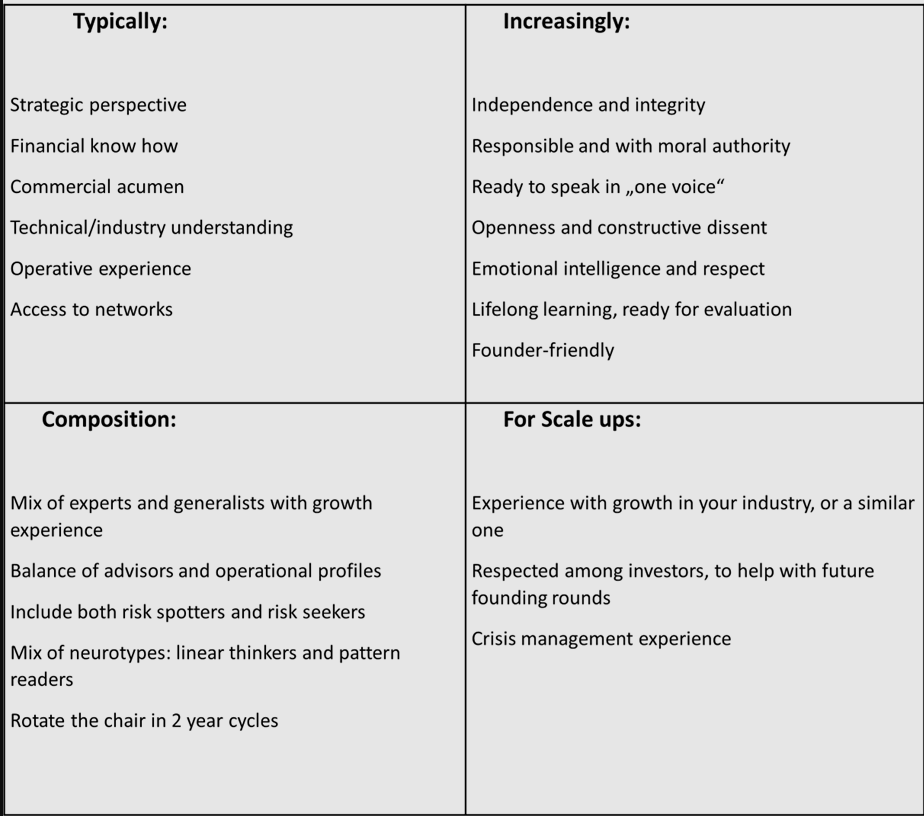

– What are the skills, attributes, personalities and neurotypes required for your board’s start up?

Use our list below to assess your board, starting with the onboarding phase. Some of our clients have changed advisors (or board members) even before the embedded due diligence of 6 months was complete. Simply, because they realized that a particular geographical experience no longer served them: disrupted supply chains have become an often-dramatic new reality for start-ups as large events such as a pandemic complicate their business models.

– What degree of diversity do you need for your board?

You will find as many opinions on this topic, as people you ask. Our approach is to use an axiom as a starting point and evolve the solution case by case, as your company grows. This way, people we advise can answer this question in a mathematical way and get past bias or the political polarization that the topic generates. We put forward the principle of requisite variety as a design criterion for the assessment of your board’s needed level of diversity. The principle suggests that to grow and flourish, a company needs to depict the full diversity of the ecosystem within which it operates.

A start up, even a fledgling at very early stages still deals with extremely high levels of complexity and need to take daily decisions affecting its success. It needs to depict this complexity — in simplified terms — in its advisory system, which is often used as a consulting system even before fractional or full-time employees and executives are hired. As the business grows, you can revisit the composition of your board in the light of the requisite variety principle, and bring in more specialist experience or a different combination of business building skills into your board.

Focus:

– Is your board focussed on what matters most?

The start-up scene is littered with dead or frozen start-ups. And advisors who got them there. In a start-up, there is no right answer. There are many right answers, depending on the level of dogma of the advisors you trust.

In a start-up, the answer to the question of what matters most can change, week on week. Are the advisors wedded to their own, possibly narrow expertise, or experience? Are they open to staying focussed on what the start-up founders know they need at any one time? Or are they still attached to what worked well for them in the last few start-ups, whilst your start up is at a different stage, with a different user base and a different go-to-market approach? Are they free of dogma, able to focus on what you must prioritize for the health and prosperity of your start up? Or are they replicating a formula they learned as a junior analyst at the VC they worked, straight out of university? Are advisors able to co-create, meaning that they are able to hold genuinely generative dialogue to evolve the best solution for the specific situation that they are in? Do they know how to challenge and support founders in equal measure, so that you have psychological safety whilst your thinking is being acid tested by experienced people?

“I was a very different investor before I lost my first 10 million. I thought I knew it all.”

Alexander Banz, VC investor and board member

-Do your advisors (or board members) consider that their primary task is to actively support the success of management, or to supervise and monitor it?

Whatever you and your advisors or board members decide, carrying out their fiduciary duties remains a key board responsibility. Rather the implication is that instead of subjecting the start-up to a perennial grilling, as in an eternal due diligence, board members balance support and challenge, yet in the service of the start up’s growth.

Advisors are human. Do they have the cognitive ability to ask questions that allow to properly define problems faced in order to identify their root cause, rather than jumping immediately to solutions? Do they master the skill of asking questions in a way that both delivers the intellectual clarity as well as build ever more trust in the relationship with them? Do they WORD MISSING insight for themselves or for all involved and energize the founders in the process? Do they pose questions to advance the company’s interests or to cover their backs? Are their contributions intended to help the business thrive and prosper, or to reduce the chances of survival so that it can be bought up cheaply by someone they are connected with? Do advisors know and master themselves? They can be traumatized too. Are they in a state of perennial paranoia, expecting you to be the next Elizabeth Holmes of Theranos? Or can they rapidly pinpoint why they feel what they do and contain their emotions if they feel triggered in an anxiety- provoking situation or board meeting?

It is important to first honestly answer this question yourself. Then, enshrine it in your board charter and make it part of what you agree with any future investors. Remember to keep coming back to this question, as it can generate its own dynamic even after agreement. No start-up survives a predominantly supervision-based mindset. It is imperative that advisors and board members see themselves as primarily supporting the founders and acting as their secure base. As and when growth spurts or external events trigger advisor’s personalities, they can dangerously revert to what they might have learned as default: command and control, push rather than pull styles of management. Unless there is a crisis, there is little reason for a board of directors to be directive and tell you what to do. A board review will helpfully raise the discussion, align, or re-align your advisors or board members and commit everyone to what you decide that your require at the stage of maturity that your start-up or scale up is at.

Dedication:

– Are they ready to commit at least 10% of their time to your start up? Are they ready to jump in at 90% when there is a crisis?

If they are not ready to commit 10% of their time, the likelihood is that you will have made the wrong choice of advisor. In case of a crisis, which in a start-up is frequent, you might need 90% of their time for a week or more (Verdon et al 2020, Nervlka 2018). Too many start up advisors on the circuit are retired, large enterprise executives or asset managers looking for an appealing start up to talk about during their conversations with family and friends. Don’t be one of them.

Dedication needs constant monitoring because things can change from one day to the next. The start-up might have to pivot to a business model to which a director cannot contribute There might be an elderly parent in need of support. A spouse might get cancer. Children may be born. One of the many partnerships you explored pays off and turns into a channel that helps you scale. The business hits a growth spurt.

– Are your advisors or board members truly pulling their weight, are they delivering what they promised?

In pillar 4, we will discuss what can happen to dynamics of boards, and how they affect a start-up’s material health. Part of the equation is invariably role conflict and shifting alliances of interests for investors or other shareholders. Start-ups are special, when it comes to upholding the dance of not staying “too far in” or “too far out” as board members balance their level of engagement with the detachment necessary to truly reflect and spot what others might be missing in the heat of the engine room. Start-ups will constantly pull at advisors and board members to be a lot more hands-on than board members should be. Partly, because board directors double up as expert consultants. So, by default, the temptation for any board member to become too operational is far greater than in any other context. It is harder to retain good oversight when that happens, and so a regular reflection to gain the higher ground is a key discipline for a start-up board member.

“I went in far too grubby & dirty today!”

Andrew Hughes, 8x exited Start up founder, Investor and NED

Conversely, it is poison for a start-up when its board members make promises at the outset, that they fail to deliver upon. Access to potential clients, help building strategic relationships with channel partners to get their products to market or developing new revenue streams, opening doors and negotiating with future investors, all of these board-powered activities, particularly if enshrined in budgets that lead to hiring decisions can even be fatal for start-ups when board members don’t pull their weight. It is often not even intentional. At the outset even seasoned advisors might experience the glow from the vision of the start-up they have joined. Over time, they might realize that they might come to dread founders’ calling only when they want something. They might grow resentful of perennially hungry founders’ request for help without reciprocation. Or of wealthy investors using them for free advice instead of giving them the typical salary of a scale-up’s non-executive. They are providing a highly sophisticated professional service that took years of their effort to build! Whatever the reason, it does not help anyone to continue a relationship that no longer works. Not everyone serves on boards because they want to “give back”, and founders must guard against assuming that successful executives and investors do not appreciate a salary. It defines the value of the service just as the start-ups product’s value is measured by its price. As you review your current set-up, is it time to reconsider board director’s compensation?

Pillar 2: Information architecture

For a start-up, building a board information architecture might appear as too grand a notion. It is key for good board work, though, no matter the size of the company. We have come across founders who have raised millions in private equity and employ shy of 100 people, and still do not produce even the basics. We are not talking about anything complex or sophisticated. We are simply taking about financial reports. To us, this must become a thing of the past. Fast.

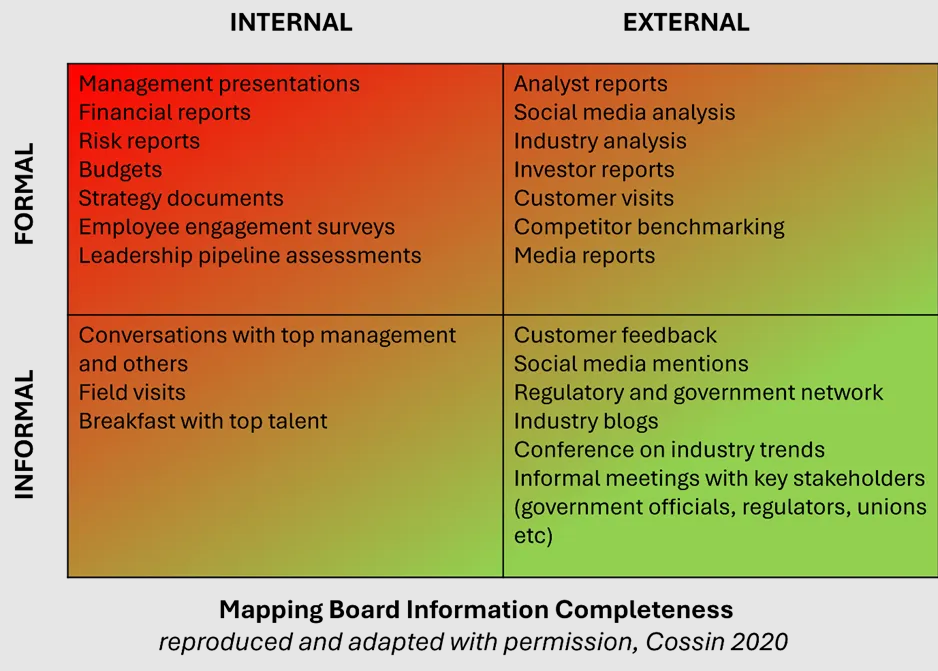

Board directors need to be informed through all channels depicted in the graph below. All quadrants on this table are typically on start-up board members’ checklists, particularly if they are professional analysts and investors by background, who predominantly focus on precisely the data gathering recommended there. Still, the weakest area for start-ups we work with consistently is in the red quadrant with the exception of strategy documents (generally well developed as part of founders’ obsession with investor pitch decks). Even with the support of their investors and board members, it is not uncommon to see start-ups, even scale-ups operating years and decades without basic financial reports. Whilst it is clear that start-ups operate at levels of risk that would be intolerable in more mature companies, it is still wise to produce and review at least a basic risk heat map and stay alert. People engagement surveys might be inexistent or considered overdone for the limited resources of a start-up. Yet even an eNPS or pulse check should be standard in a start-up. They are easily implemented and key to any balanced score card for a board. Reliance on Glassdoor, indeed or kununu is a poor substitute. Leaving the reputation management and sense making about what is really happening in the company to disgruntled employees who might or might not have been a good fit to start with.

A word on tech for boards. Why is it that in 2024 start-ups still use files sent via email to communicate with their board members? Tech start-ups? Isn’t it time that we used tech in the boardroom. To its full potential? To us, it starts with the basic, safe and secure information repository of a board portal. This should no longer be optional once you have crossed the line into accepting serious funds from professional investors, whether private equity or VC. This should be a hygiene factor at this stage of maturity.

A promising approach to using tech to enable better board discussions is Zeck, a cloud-based platform which replaces the traditional board deck with an interactive website. By providing updates and clear decision metrics, as well as a collaborative workspace, board members come to the meeting well prepared to engage in the discussions that lead to good decisions — rather than simply listening to the same information they read in the board pack since the Chair isn’t sure who has read which parts of the deck in advance.

“What is a board portal, Claudia? And why do you keep talking about it?”

First-time Scale up founder, 10 years into the journey

(Not a lone voice, we hear this all the time.)

Pillar 3: Board structures and processes

This pillar of good governance is the easiest to dismiss, as a start-up. We highly caution against it, even while we understand founders tuning out when they hear the obsession of governance experts with committee structures. Clearly, a start-up is — and must remain — a lot more fluid than the more mature organization. This is true for the whole company, let alone for the board. A start-up board must stay as alert as possible and might need to switch topics much faster than more mature company boards. Committees make no sense in such an environment.

Still, the start-up founder must work on some of the key processes required for board quality. In our experience they are:

Agenda setting, board meeting preparation, minute taking & circulation

Strategy

Risk

Tracking the Decision-making effectiveness of the board

Board director talent acquisition, onboarding and assessment

Management performance review, business review

Records of board communication including information to stakeholders and shareholders on governance topics

Monitoring accounting, fiscal, regulatory and legal requirements relevant to the start up

Some of these processes, including the legal and financial ones can be outsourced to legal advisors and fractional CFOs. They can be covered by the skills mapped and the talent sourced through advisors and board members. They will need to expand and upgrade all along the growth stages of the start-up. The governance-conscious founder will go through the list above and ensure that, ahead of each major liquidity event, founding round or exit, all key processes and their documentation are in order, as new owners might take over or join the board table.

One of the key decisions to make in upgrading the governance framework in a scale-up is the decision about introducing a formal audit process. If brought in too early, it risks creating an administrative burden that can not only weigh down an operation that needs to stay agile, it can also dangerously distract from the much needed focus we covered in pillar 1. Accompanying the start- up on its way to maturity, balancing the need for continuous innovation and growth with the need for oversight and control, including fraud detection, are a key responsibility and contributor to high performing boards. This ideally falls to independent directors who should be brought into to a start-up board as soon as possible. The added benefit of the independent director, for a start-up, is that they can provide crisis leadership, where founders are all too often unable to emotionally detach sufficiently from their own creation to take sound decisions that are free of relationship entanglements or attachments to products or business models.

Pillar 4: Group Dynamics and Board Culture

All good governance efforts on the previous three pillars can come to naught — and in the high-risk environment of start-ups even within days or hours — if the quality of interaction of board members becomes dysfunctional. Boards are relational structures. This means that it is not enough to look at individual director’s track record, traits and skills, and put them together with a mechanistic mindset. Because boardrooms are the most anxiety-provoking spaces in any company, yet heightened in the perennially fast-paced, high-risk world of start-ups, the way in which the board works together takes on added importance. Founders are often surprised that we do not insist on the entire governance curriculum to help them build their governance framework. We do insist on a minimal level of literacy in group dynamics, because they can create a booster effect, or sap energy or even tear the fabric of your board apart.

Start-up boards disregard board dynamics and the importance of establishing a healthy board culture at their peril. Ideally, they need to find advisors with functional or business building expertise — who are also skilled at navigating the human interaction side of board work. Ideally, they need to have developed their coaching and mentoring skills and be accomplished facilitators who can guide founders through basic processes of building a robust social fabric, able to preserve their board’s focus, dedication, and rationality.

Forming an Advisory Board is a practical test of the dynamic of your board. Before you commit to an appointment of a director to the legal board, this can be a helpful way to see them contribute, or detract, in a group. Consider the guidance by the European Champions Alliance (ECA, 2021), which recommends the creation of an Advisory Board soon after incorporation.

This is one of the most stimulating yet equally polarizing pieces of content we share with our coachees and students. Why? Because opinions divide around the true value of advisory boards. In theory, there is nothing wrong with the idea of bringing together a group of otherwise well-qualified experts and business leaders. The more complex the environment, the technical, social and political field within which the start-up operates, more listening needs to be done, and less repeating of previous advice. This can already be hard to do when the advisor is talking to founders bilaterally. In a group situation, when facing the unknowable, perhaps because there is an entirely new category of biotechnology or a pandemic to navigate, advisors can lose their self-control and revert to power play, overly directive advice and competing with other advisors about who can add more value to the start-up. Depending on the power balance in the board and with the founders, advice can become a competition between advisors. Board meetings can become mock legal board meetings, with a controlling rather than supportive tone. Advisory boards can convene meetings without the founders to discuss all that appears wrong to them about the start up. They can completely fail their assignment: guide and support the founders.

This is not a good place to be when growing a business, and can weigh the start-up down, rather than add value. Particularly pre- or post-Series A start-ups, and highly experienced angel investors tell us that they prefer going from working with a free-flowing constellation of individual advisors towards directly setting up their legal board, or upgrading the initial founder-based board with externals.

Ultimately, the founders need to decide whether to follow ECA’s guidance, which is also shared by Feld et al, 2022. Will advantages outweigh disadvantages? Is there are risk that accomplished people will get lost in their own group dynamics?

One way forward, if the decision is for an Advisory Board, is to consider Feld et al’s suggestion to convene Advisory Board meetings in a more ad hoc fashion, rather than treat it as a legal board with a regular meeting schedule. The acid test question must be: is the Advisory Board truly serving the founders?

Whichever choice founders make, we recommend that you first invest in bilateral relationships with advisors until you have developed the board charter, and created enough traction that helps build your own power base capable of navigating the group dynamics and power plays that invariably develop when you put board members together.

It is especially hard to contain the anxiety a high-risk environment produces. Instead of sharing war stories at web summits and start up events, complain about their dysfunctional boards behind their backs, we strongly recommend that start-up founders get on with the business of building a healthy fourth pillar of good governance, so that dynamics don’t detract from the primary task of a board: to facilitate and deliver rational, good decision making.

Source: Cossin, 2020, High Performance Boards

In conclusion: How to ensure the board stays relevant to the start-up as it grows? We recommend regular board reviews, at least around major liquidity events, based on the 4 pillars methodology. A board evaluation is a helpful tool to identify areas of strength to lever as well as diagnose gaps that may create vulnerability- and these will certainly change as the company evolves, and its strategic ambition and risk appetite shifts. Board evaluations are also helpful in that it makes explicit a common view and understanding of the role of the board as a whole, its current areas of opportunity and challenge, as well as the skills, qualifications and experience that the board need to ensure its members have.

6 Get your board future-ready

We have both worked with and studied the oldest companies in the world. Which have changed industries in the space of 700 years and more. Everything points to the same: developing both foresight and combining that with containing the top decision-making body’s fears are the key for sustainable innovation over such a long horizon. To achieve this level of future fitness, you must keep working out.

How do you train your foresight? You might attend all the right conferences and regularly speak with industry colleagues, world class experts and founders with multiple, strategic exits. You might regularly seek out reverse mentors who are years and even decades younger than you. What else can you do? How does that translate to the quality of your board’s decisions?

Future-readiness indicators we watch can range from refreshing who sits at your boardroom table, what insights or expertise they can specifically contribute in relation to the future of your industry, and whether you are holding the right type of future-focussed conversations at your meetings. The horizon we have in mind here goes well beyond a typical search for a non-executive with growth experience who can help your scale up reach its ambitious 5-year business plan.

You can have your antennae in the market and be deeply immersed in all the latest tech trends. You might be shaping the next big thing your competitors will want to emulate, if you are successful in your go-to-market phase this year. Are you asking the right questions during your meetings, though? And is your board keeping pace when it comes to making investments or appointing new directors? How do you mitigate tech debt or talent debt risks when the tech your company currently uses might be perfectly fit for purpose — in the present? How do you keep ahead?

How do you contain director’s humanly unavoidable fears in the face of the unknowable? Instead of relying on past education and track record, on annual strategy and board retreats, we believe that you must keep your fingers on the pulse of your board, meeting by meeting. Future-fitness is not an annual exercise. It is a daily practice.

Today, we use tech to support this process. Your experience, your people and business judgement are no longer enough. There are enabling technologies in our toolbox, in particular, that address future-readiness. No, a board portal is necessary but not sufficient.

FitBoard is a next generation governance tool, to dynamically assess and systematically develop the future-readiness of your board. We achieve this both by using it for discovery of your starting point, as well as by nudging you on towards addressing any gaps or development needs, one meeting at a time. To aid the discovery, there are a core of future-fitness criteria built into the app, which include capabilities of board directors, as well as technological, strategic, investment and supply chain-based considerations that determine the competitiveness and future success of the company. Once the starting point, the baseline is set, the pathway of the board, in app, unfolds dynamically, along its meeting calendar. The board is encouraged to regularly reflect and build on recommended behaviours for high performance. Any red flags are anonymously raised and instantly make it to the Chair’s dashboard, even between meetings. AI is accelerating the process of personalization of just in time, actionable recommendations for each director, and the whole board. This allows for the monitoring of the quality of decisions, as they go from preparation to implementation, and from strategy to execution.

What next is on our horizon? We believe that in future, start-ups, their investors, whether private equity, VC, with a family business or large enterprise ownership, need to crack an important conundrum. One that we have been monitoring since “disruption” became the word of the day in the mid-2010s. One that we have been watching since we, following on from that, started to actively accelerate innovation and digitalization by bringing in younger and more tech savvy directors onto boards. How do you reconcile the monitoring of KPIs that are both about laying the foundations for value creation tomorrow, as well as about maximising value extracted today? Only 10% of leaders who participated so far can do both well — at the same time. It is this ambidexterity we believe is key for the selection and the development of the leaders and board members who will steer start-ups successfully towards maturity and a sustainable future. The leadership pipeline assessments the board needs to be monitoring for the start up’s human capital renewal strategy will need to be able to assess the degree of alignment between leadership capabilities and the organization’s long-term strategic needs. Based on this type of future-readiness diagnostic, nomination and education work for future talent, including individual learning pathways for executives and non-executives will see a quantum change.

About us

Sophie works with board members and aspiring board members from around the world to design and deliver board education programs, as well as governance advisory, in her role as the Associate Director of the IMD Global Board Center. She has conducted board reviews with a number of public and private organisations, including, as well as facilitated strategy retreats for several boards.

Claudia coaches entrepreneurs, board-ready leaders and non-executives in becoming high performing company stewards and innovators. She brings her design, facilitation and mediation skills to board evaluations and strategic board retreats for her clients. As a cultural transformation expert, she brings a whole-company perspective to scaling businesses and leads the development of a next generation governance platform, FitBoard.ai. In 2022, she joined IMD’s board centre as an affiliate, where she also teaches governance for entrepreneurs.

Reading

1) European Champions Alliance (2021) ECA Early Stage Governance Guide: An effective lever for the development of start ups. Self-published, link to download here

2) Brad Feld, Matt Blumberg, Mahendra Ramsinghani (2022) StartUp Boards: A Field Guide to Building and leading an effective Board of Directors, Wiley, Second Edition

3) Roch Ogier, Michael Hilb, Virginie Verdon (2020) Start Up Governance in Switzerland: practical guidelines for founders and board members. Self-published, link to download here

4) Didier Cossin (2020) High Performance Boards, Improving and Energizing your Governance, Wiley, Second Edition upcoming

5) Charlotte Valeur, Claire Fargeot (2022) Effective Directors: the right questions to ask (QTA) Routledge, open source download link here

6) Jana Nevrlka (2018) Cofounding The Right Way: A practical guide to successful business partnerships, Panoma Press